AT 9:30 PM ON A THURSDAY, Skip’s phone rang. Not his cell phone, but rather his office phone, the phone only the sales guy from Rawlings ever called. The ring interrupted the lighting of a cigar. Not a Cuban, but a decent one nevertheless. Six games into the season, it was a bit early for a cigar, but his senior closer had blown a two-run lead in the ninth, leaving the team winless heading into league play next week. Likely, a long season lay ahead. Skip stared transfixed at the pulsing light on the phone, then he noticed the words. President’s Office. This was a campus call from the president’s office. Curiosity got the better of him.

“Hello.”

“Warren?”

No one, except his wife, called him Warren. The voice sounded familiar but he couldn’t place it. “That’s me.”

“It’s Ankit. I need to speak to you.”

It registered. Ankit was President Patel, the head honcho on the campus, ostensibly Skip’s boss. But there’d been five presidents in his thirteen-year tenure as head baseball coach at this small Los Angeles D2 school. And one league championship.

“We are speaking.” Skip regretted sounding like a smartass. The blown save wasn’t the new president’s fault.

“In person. I’ll be there in a few minutes.” The president hung up.

Skip put the receiver down. It was now 9:32. He put the cigar and matches back in his desk.

At 9:38 pm, President Ankit Patel, PhD, arrived, his medium frame not filling the doorway. Skip considered that it had to be at least a third of a mile across campus, and thus the President must have walked at a brisk pace. Skip stood and motioned to the seat in front of his desk. “President Patel, please.”

The president sat. “Please call me Ankit.”

Skip sat back down, wondering if the President had ever been here, before remembering he’d come by on his welcome tour of campus, not even three months ago. He was deciding if he should use “Ankit” or not, when the President spoke.

“I need your help. Urgently.”

“What can I do?”

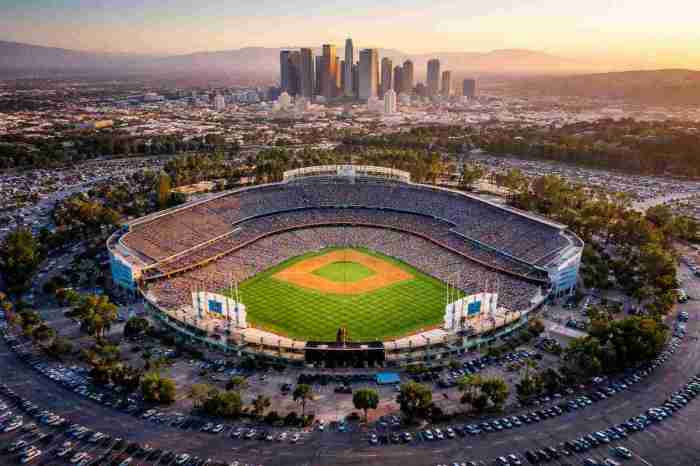

“You know the Dodgers game in two weeks?”

Skip knew it all too well. It was their school’s night at the game. One quarter of the concession profits would go to the baseball program. A great fundraiser, in truth, but always a production. Skip had a long list of phone calls to make. “Yeah,” he said.

“Their publicity person called my office today. She asked if I would throw out the first pitch. She said it would make for great press.” The president paused and wiped his brow with a handkerchief he produced like a magician.

Skip ignored the president’s apparent magical abilities. “That’s great.”

“That’s awful!” The President nearly shouted.

“Why?”

“I’ve never thrown a ball. Ever.”

“You mean a baseball. It can’t be much different than a …” Skip paused. Was he crossing some cultural or racial line here?

“Cricket ball?” The President completed his thought.

“Right,” Skip said.

“No. I’m the only Indian kid in history who never played cricket. I need your help. You need to teach me how to throw.”

“What?”

“You are a coach, right?”

Manager, actually. Skip thought but just nodded.

“Well then, teach me how to throw. In private. How’s Saturday about this time?”

Saturday night? Skip thought about two days from now. Morning practice, afternoon beer and couch. But in the evening, his wife was ushering at a community theater. “I’m free.”

“Good. See you here. 9:30. Tell no one.” President Patel pushed his chair back, turned on his heels and left, white shirt crisply tucked into suit pants.

Skip heard his shoes clack on the tunnel toward the dugout and marveled that the President had found him here; even some of his players had trouble finding the office. He fingered the drawer with his cigar. 9:45. He should go home.

“You getting axed? ‘Bout time, I’d say.”

The baritone voice made Skip jump. “Jesus,” Skip said.

“Fess up, I saw the President leave here. You must be fired.”

Skip took in the full view of The King of Dirt, or King for short, their field man, best infield in all of college baseball. King was broad, he filled the doorway and his dark complexion made it hard to discern his expression. “Dammit King, what are you doing here?”

“C’mon Skip. You know me. Can’t sleep, work nights.”

Skip knew this. “I’m not getting fired.” He went on to violate the President’s dictum and tell King the story. King could keep a secret.

“That’s hilarious,” King said. “And you said Saturday night?”

Skip murmured “Yes,” as if he said it low, this whole situation would disappear into the ether.

“I’ll be here. Can’t wait for this show,” King said. Then he left.

At 9:52, Skip lit the cigar.

Skip got to campus at 9 on Saturday night. Miguel, the weekend security guard, questioned him. “Skip, I know you don’t sleep, but Saturday night?”

“League starts Tuesday, got work to do.” Skip hoped he sounded convincing. He wondered how he’d keep Miguel away from the field. Not my problem.

On the field, he considered the problem of lighting. He’d imagined the President pitching by moonlight but clouds made that impossible. Running the full field lights would draw attention. A solution hit. He parked the golf cart behind the mound and ran the 120 foot extension cord into the dugout. The headlights were just enough. King, who was probably lurking around somewhere, would bitch about his grass (he was the King of that too). He grabbed two buckets of the oldest balls and set them on the side of the mound.

The President showed up at 9:30 sharp in a dark Adidas tracksuit and running shoes. He walked toward Skip with uneven stride, his face showing no emotion. Skip tried to remember anything about him during the four months he’d been on campus but came up blank.

“Good evening, President Patel. Are you a runner?”

“Five miles a day. And please, call me Ankit.”

Five miles a day? Skip felt the gentle push of his belly against his baseball pants. He wasn’t meeting his New Year’s goal of walking three miles a day. “We all got nicknames around here. How about I call you ‘Prez’?” A bit lame but best he could do on the spot.

The President smiled. “That’s good.” Then he looked toward the mound and the smile disappeared.

Prez had never thrown a ball so Skip started him with some windmill exercises. He’d never played tennis either but his form was decent considering, maybe this wouldn’t be so hard. Skip then got on the mound and lobbed a few balls toward home, talking Prez through his motion and follow-through. The balls made a grating smacking sound against the wooden backstop, Skip wished he’d been able to grab their backup freshman catcher. Then it was Prez’ turn.

Prez, who’d been attentive and almost relaxed during the stretches and instruction, looked scared on the mound. He stood rigidly staring at the plate, a slight wobble in his knees.

“I’ve never seen anyone fall off, except the pitcher for the Giants but that was during a San Francisco wind storm,” Skip said, trying to lighten the mood. Prez grimaced. “Just give it a try,” Skip said.

Prez raised his front leg, shook a bit on his back leg – there was no wind but it didn’t seem impossible that he might fall off, his right arm reached back, front leg dropped, he windmilled the arm, and let the ball fly. Well, he let the ball skitter. It traveled about 15 feet in the air approximately 45 degrees off the path to the plate, landing in fair territory halfway to the third base line. The Prez looked at Skip, lips pursed.

“That’s just one, we got two buckets. Remember to bring the arm through all the way. The ball will follow the path of your arm. Imagine the line from your release point going straight over the plate.”

Prez nodded and picked up another ball. Halfway through the first bucket it was clear this would be a difficult task. The follow-through was better and Skip had convinced Prez to throw harder so balls were going in the general direction of the plate but (still) none within ten feet of the target.

“How’s the arm?” Skip asked, he was starting to feel a slight headache from the sound of the balls.

“Okay.” But Prez rubbed his elbow as he said this.

“Let’s take a break anyway.”

Prez nodded and the two men stood on either side of the mound. Prez looked miserable and Skip had no idea what to say. Then a deep voice.

“What’s all the racket out here?”

King strolled toward them from the right field bullpen. He was in his uniform, baggy cargo shorts and a gray hoodie, its logo long faded. Skip glanced at Prez who looked tense and confused.

“That’s King, our groundskeeper, he works nights, but not Saturday.” Skip glared at King who was now in the infield.

“Nobody here’s to bother me on Saturdays,” King said. “President Patel, I didn’t know you were a baseball aficionado.” He smiled broadly and Skip saw Prez’ jaw loosen. King had that effect on people. Skip explained the situation as if it were new to King and King assured Prez of his discretion.

“Let’s try round two,” Skip said. Prez slowly bent and took a ball looking at it as if it were the proverbial poisoned apple. “Wait a sec,” Skip said and he jogged to the dugout. He returned with a glove and threw it at King. “Make yourself useful.”

Prez threw balls for the next ten minutes, Skip by his side, commenting on his form and offering pointers every three or four tosses. King stopped about half of the pitches as they were now getting closer to the plate, if not over it. He also kept up a steady banter, “You got this Prez. It’s all you.” And “Bingo” when he caught one in the air only a foot or so off the plate. Prez smiled.

“Let’s stop here,” Skip said.

The three men sat in the dugout drinking lukewarm orange Gatorade that Skip had found lying around.

“It’s not beer,” King said.

“Next time,” Prez said. Both men looked at him. “I’ll bring some,” he said, sounding presidential. “I prefer blondes over IPAs by the way.”

King let out a roar. “The President prefers blondes. That’s rich. And bring whatever, I heard this man,” King looked over Prez toward Skip, “drinks Bud.”

Skip snorted. Bud was fine. And he couldn’t believe he was sitting here on a Saturday night between two PhDs, trying to teach one how to throw a baseball and listening to the other impugn his taste in beer.

They scheduled their second, and final, session in a week’s time.

“I have to get back to the office,” Prez said, as if it were 10:30 am on a Monday morning rather than a Saturday night. He marched off. Skip and King looked at one another.

“Think he’ll do it?” Skip asked.

“In front of 30,000 people? Not a chance,” King said.

The team’s league opener on Tuesday afternoon was abysmal, they were chasing five by the end of the second. King sat in his usual spot at the far end of the bleachers past third base. When they finally scored on a solo homer in the fifth, Skip glanced at King who pointed to his right. Skip turned to see Prez sitting in the middle of the bleachers, the VP of finance next to him. Eyes met and Prez nodded. He was gone by the 7th.

The team lost a close one the next day and got their first league win on Thursday when his best recruit gave up no runs over six. Skip ran light practices on Friday and Saturday. They were on the road next week, but not before the Dodgers game on Monday.

Skip hit LA traffic on Saturday night and arrived five minutes late to the field where he saw lights from the golf cart. He was confused, the key was in his pocket. Then he realized. King had his own cart for moving supplies. Sure enough, King and Prez stood next to the mound, both wearing the same outfits as before. The Prez had a small cooler at his feet.

“You’re late,” King said, his voice echoing in the clear night. “You should run laps.”

“Grab a glove,” Skip said. “How’s the arm Prez?”

“Good, I did the windmill exercises all week.”

“Let’s get at it. Only one bucket this time, can’t overwork it, game’s in two days.”

Prez’ inaccuracies were more consistent this time. When he reached the plate, it was high and wide but mostly catchable. “That’ll work,” Skip said, on a ball that King caught at his nose. If he took something off the throw, the pitch would be right on in direction but bounce two-to-three feet in front of the plate. King let those roll. “Combine those throws and you’ve got a perfect strike,” Skip said, aware that there was no coaching in that statement.

With three balls left, Prez stopped and looked and looked at Skip. “Three strikes you’re out, right?” Skip nodded. Prez picked up the first ball on looked at it intently. Then he set, raised his arm, and lobbed it right over the plate into King’s glove.

“Hot damn!” King shouted. Skip turned to give Prez a high five but he already had the next ball. Two more strikes followed.

The men sat, craft beers in hand, on the perfect infield grass in lawn chairs from King’s cart. “You did good Prez, you’re ready,” King said.

“Hope so.” Prez took a long pull on his beer, finished it, tossed the can on the grass, and reached for another one.

“Hey, watch my infield,” King said.

“You always work at night?” Prez said in response.

Skip saw King’s mouth open then close before answering. “For most people, it’s a day job but I don’t sleep too well at night and then this guy is outta my way.” He pointed at Skip.

“Best infield in the country,” Skip said, almost adding a quip about King being a pain in the ass.

“You’re an insomniac?” Prez asked King.

“You could say that. I got my demons.”

“Want to share?”

Skip’s arm stopped midair. He tried to remember if Prez was a psychologist of some sort. He looked at King who stared at home plate and then began to speak. “I was a doctor like you, PhD. The only Black professor in agriculture at my university. Probably the only one in the whole damn state.” King talked about his lab, and grants, and being a year from tenure when he up and quit. “It was just too much. I wasn’t happy. But it’s the letters I still think about.” Prez gave him a questioning look. King explained that a few months before he left the job a major magazine did a story on him. “You know Black guy breaks into a white discipline kind of thing. It was widely read. I got emails from all over the country, Black undergraduates wanting to come study with me. I let them down.” He stared at the can in his hand.

“And now we have the best infield in the country?” Prez said.

“This guy thinks so, but he likes Bud, so take it as you will,” King said.

Skip punched King in the knee. The men were silent, the drone of the cars on the freeway a soundtrack for their thoughts. Prez spoke. “Maybe we could fund an internship. Bet there aren’t too many Black groundskeepers around.”

“Damn,” King said. “that’s an idea. You know anyone on the campus with money?”

“I might.” Prez smiled. When he spoke next his voice was lower. “I work a lot of nights too. I only disappointed one person. My dad. He wanted me to be a real doctor, a surgeon. He never understood cognitive science.”

Cognitive science, that’s it, Skip thought.

“How’s he feel about you being Prez?” King said.

“He died a week before I got the job.”

“That’s rough,” Skip said.

King raised his can. “To expectations, great and small.” The men toasted. A siren wailed far off.

Skip finished his beer and rejected the idea of a second. “It’s getting late,” he said.

“You’re not leaving. Me and Prez poured our hearts out. Your turn. You’re here too many nights,” King said.

“Fuck,” Skip said. He paused. Then felt something cold on his hand. Prez was handing him a can. He opened it and took a long drink. It was better than Bud, rich and a tad sweet at the finish. “My brother. The usual story, can’t keep a job, drugs, broken family. I half-raised his kids. Even hired him. And fired him. Remember King?”

“Yeah that was cold. But he was the worst equipment manager ever.”

Skip laughed. “He was awful. We had to play a game in T-shirts once. But, he’s my brother and all those years of Catholic school.”

“My brother’s keeper … even a Hindu knows that one,” Prez said.

Skip nodded and raised his can. “To Hinduism, Catholicism, and whatever’s in between.”

The insomniacs drank.

Twenty minutes later they called it a night, each man leaving the field in his own direction. Prez turned around after a few steps. “King, will you be there Monday night?”

“If this guy gives me a ticket.”

“Come to work Monday – during the day – and I’ll see what I can do,” Skip said.

“You got this Prez,” King said.

Skip and King had good seats along the third base line. It was early in the season and the stadium was only half-full at the playing of the national anthem. Then the Dodgers' announcer blared about it being their night. King had even traded his hoodie for a college sweatshirt. Prez walked out to the mound in a campus tracksuit and the same running shoes. He looked sharp and relaxed. The catcher gave him a fist bump, handed him the ball, and jogged back to the plate. Prez was alone on the mound. Skip’s arm twitched and he looked at King who raised one eyebrow, face impassive. Prez rubbed the ball and stepped on the rubber. He raised his front leg and brought his right arm straight back. Good form, Skip thought. The windmill motion was also good but Prez released the ball far too late. It hit the ground maybe twenty feet in front of the plate, and took a bounce away from the catcher who could only watch it roll away. “Ouch,” King said. But then. But then the Prez did a thing. A dance move. The Macarena or the Nae Nae or something. “Holy shit he didn’t,” King said. The crowd roared. The catcher and Prez met halfway to the plate for a high five. The catcher handed Prez a different ball. The video monitor replayed Prez’ move and the crowd roared again. Skip threw his arm around King. “Some things you just can’t coach.”

The men met in the parking lot, Section G, as planned, after the 3rd inning. King and Skip, standing under a light pole, spotted Prez’ brisk walk right away. He had a ball in his right hand. “What the hell was that?” King said as Prez got within earshot.

Prez’s teeth were white beneath his smile. “I had pretty good coaching but I figured I should have a backup plan just in case.”

“Pretty good?” Skip said as he gave Prez a half hug. “Amazing, no one – except us of course – will ever remember how bad that pitch was.” King hugged Prez as well. “And what, were you a dancer on your way to not being a surgeon?”

Skip shot King a look, but Prez smiled broadly and said, “Too much late night MTV.” They bantered a bit more then decided to call it a night.

“Nobody is going to work, right?” Prez said.

“Is that an order?” Skip said. “I gotta prepare for a road trip.”

“Go home and pack. Are you back Saturday, maybe we could meet again?” Prez looked at both men. “We could discuss the internship.”

“And pitching, someone needs it,” King took the ball from Prez’s hand and made the windmill motion.

“That’s true, the Angels might call next,” Skip said. “I’ll bring the beer.”

“Angels? Is that some Catholic thing?” Prez said.

“Not Bud,” King said.

The men laughed. King tossed Prez the ball, which he caught.

In his car, Skip checked his GPS. Traffic, thirty-seven minutes from home. It had been far too long. He knew what he had to do.

He dialed his brother.

— FRANCOIS BEREAUD

Back to the Review >